Solomon Alexander Levenston's (1858-1897) Medical Notebook

Differing

Medical Practices

in a Glasgow Victorian Family

Dr. Kenneth Collins MPhil PhD MRCGP

International Congress on the History of Medicine

Glasgow,

September 1994

Medical botanists formed a major and growing element in the delivery of medical care in Victorian Britain supplementing the provision made by qualified physicians. Medical reform, introduced into Britain from America in the middle of the nineteenth century, combined botanical treatment, with a strong emphasis on the use of lobelia, with physiotherapy. The Levenston Family in Glasgow represented these two elements comprising both qualified orthodox medical practitioners and unqualified practitioners of medical botany. Samuel Levenston graduated MD at the University of Glasgow in 1859 and had a long career in medical practice in Glasgow after years of work as an unqualified practitioner. His father and brothers were active in medical botany in Glasgow, Edinburgh and Dublin often posing as doctors but without the appropriate qualifications.

This paper examines the history of the Levenstons and contrasts the practices of the different members of the family showing the relationships within one family between a university trained physician and medical chemists. The surviving Glasgow pharmacopoeia of Solomon (Alexander) Levenston illustrates the style of his medical treatments setting the practice of his medical botany into context.

In the middle of the nineteenth century chemists and medical botanists represented a major proportion of the estimated 6,000 irregular medical practitioners in Britain, dispensing medical treatments over-the-counter. Medical care was often expensive and thus available only to the wealthier in society. The growing band of chemists and druggists with their middle class status, developing professionalism and expertise set them apart from other fringe practitioners. Rich, and poor often supplemented their regular medical care by resorting to unqualified practitioners drawing on traditions of folk remedies, astrology and even magical practices or using new sciences as homeopathy and medical botany, sometimes supplemented by showmanship or trickery.(1)

New systems of medical botany began to appear in Britain in the middle of the nineteenth century with some based on revolutionary ideas originating in America. One such system was derived from the writings and medicines of Samuel Thomson, who made good use of lobelia, cayenne pepper and steam vapour baths. Thomson's system, the first to revolt against orthodox medicine in the States in the nineteenth century, was a great commercial success and others were soon attracted into this growing market.(2) Thomson himself claimed credit only for lobelia using many medicaments already familiar to users of botanical products. His only real contribution to therapeutics was to arrange his drugs into a "course" and to recommend doses.

In Britain George and John Stevens of Bristol claimed to have brought over American botanic practices. John Stevens described his system in his book Medical Reform or Physiology and Botanic Practice for the People and it was the emphasis on popular medicine on which the botanic practitioners relied for their success. Medical reform had its British base in Nottingham but there were many adherents in Glasgow as regular advertisements in the Glasgow Herald for this period show. The medical profession reacted strongly to the challenge implied by the new herbalists and medical botanists whose success threatened their established position. Some of this rivalry between the doctors and the medical botanists can be traced out within the Glasgow based Levenston family whose members included both irregular and orthodox practitioners.

The Levenston family had long been settled in England where the head of the family Michael Jacob Levenston (1799-1864) had been born. His youngest son Henry was also born in England in 1837, but is thought that they moved first to Edinburgh before settling in Glasgow. (4) The Levenston family were probably all involved initially in the same herbalist business when Michael Jacob Levenston arrived in Glasgow with three grown up sons, William. Solomon Alexander and Samuel in addition to his younger sons Michael, Joseph and Henry and a daughter Sarah.

The Levenstons were well represented in Glasgow by the 1850's with the first records of their activity in the city appearing in the Post Office Directories by 1852. In that year, Dr. Samuel Levenston (1823-1914) had his home at 23 London Street but with a business address close by in a former tobacconist shop. Although using the title of "Doctor" Samuel Levenston did not qualify in medicine until 1859 when he graduated MD from the University of Glasgow. Thus, he would appear to have been known as a "doctor" even before beginning his medical studies, as a mature student at a time when it was not uncommon for undergraduates to enter university at the age of 16 years, in about 1854. This surely indicates that he began his 'medical' career in Glasgow in the family tradition of 'irregular' medical botanical practice only switching over to 'orthodox' medicine after completing his medical studies at the University of Glasgow. As a Jew, Samuel Levenston would not have been able to graduate MD in England because of the presence of religious tests in the universities there which persisted until 1872. The Scottish universities had no such religious tests and attracted Catholics, English non-conformists and Jews who were unable to study and graduate in England. (5)

It must have taken some time for the separation between Samuel's herbalist past and his medical practice to be effective. Even after his graduation, his herbalist father and brothers used his surgery premises for their own activities for a while. One example of the heightened respect accorded to Samuel Levenston's decision to study medicine was the invitation, in 1853 while he was still an undergraduate, to serve as one of the three trustees for the new synagogue in Glasgow's George Street, now the site of Strathclyde University. (6) This was the first major project of the small but growing Glasgow Hebrew Congregation and Levenston's fellow trustees were businessmen more closely involved with the work of the Jewish community. Indeed, Levenston was the only Jewish undergraduate in the city at the time as the younger Dr. Asher Asher, a former Honorary Secretary of the Congregation, had completed his medical studies in 1855 and was now working in the mining town of Bishopbriggs just north of Glasgow. (7) Samuel Levenston again served as a trustee for the Glasgow Hebrew Congregation when a handsome new synagogue was erected at Hill Street in Garnethill in 1879 following the growth in the local Jewish community during the 1870's.

In 1855 Michael Jacob Levenston opened a herbalist business under the name of Dr. M. J. Levenston at 42 Stockwell Street in the city centre. For the next decade the business was in the name of his son, listed in the Post Office Directory as Dr. William Levenston, and described as a surgeon accoucheur. After 1858 both Michael Jacob and William had to drop the title "doctor". In that year the new Medical Act regulating medical training became law and clear guidelines were laid down for the first time for those entitled to style themselves doctor of medicine. The Medical Directory For Scotland (1856) had listed both Michael Jacob and William in a supplementary list of practitioners who had consistently failed to supply details of their qualifications. That their names fail to appear in later editions of the Medical Directory confirms their lack of a proper medical qualifications. This stripping of their veneer of assumed medical qualifications left them confirmed merely as medical botanists, and unlike Samuel, now able only to dispense herbal medication.

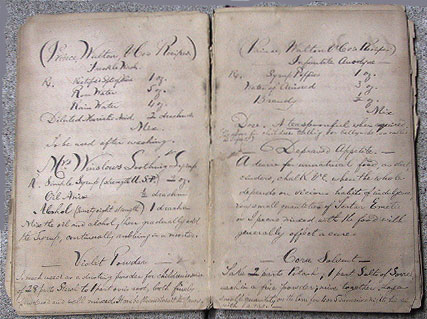

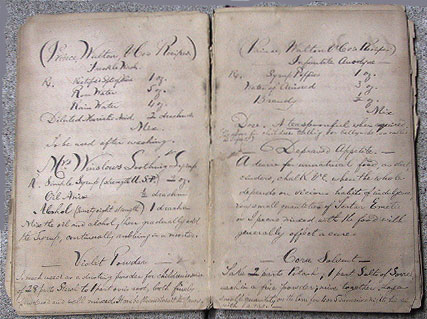

Solomon Alexander Levenston (1830-1887) also claimed medical qualifications for which he was not entitled. The cover of his pharmacopoeia, from his business at 150 Argyle Street, Glasgow during the l850s, shows him describing himself as Dr. A. Levenston FRCS. (8) His brother Samuel Levenston's decision to enter the Glasgow medical school may have been affected by the perception of an improved status and income to be derived from working as a qualified rather than as an unqualified doctor. However, in the days prior to the Medical Act of 1858 it would have been difficult for the public to differentiate between regular medical practitioners and those who claimed medical qualifications for themselves without justification. There could therefore have been some overlap in the clientele of the qualified and unqualified Levenstons, not an unlikely circumstance at a time when physicians were known to practise free in chemists' shops in return for a share of the profit on the dispensed medication. (9)

Solomon Levenston's pharmacopoeia (see appendix) lists over 40 remedies for such ailments as gonorrhoea, chancre, buboes and other sexual disorders, neuralgia, nervous disability and intestinal complaints as well as treatments for hair loss and to make mustaches 'luxuriant'. There are a number of general tonics many of them based on herbal and botanic remedies. Solomon Levenston did not lay claim to have originated these preparations and credited many of them to a local medical botanist Craufurd Muir Mackay while others were imported from Price, Walton and Co. of Cincinnati, Ohio in the United States of America. The collection of remedies has no mention of lobelia or steam used in medical reform but the presence of American products and American botanical ingredients such as sarsaparilla, quassia and podophyllin was obviously important. In any case we have noted that the success of the 'new' medical botanists was in their challenge to the established medical profession and in their use of a comprehensive formulary.

Solomon Levenston, now unable to pass himself off as a real doctor, left Glasgow to settle in Dublin in 1859 where he continued to carry on a botanical practice. (10) While Solomon's wife dealt there in second-hand clothing Solomon Levenston gave private tuition in physiology and other medical subjects, and afterwards ran a dispensary in High Street with a reputation for holding the patent for a cure for venereal disease. Solomon was soon joined in Dublin by his father Michael Jacob who died there in 1864. This combination of activities, combining medical and botanic treatment with physiology suggests that Solomon Levenston may have been involved in medical reform in Dublin.

The Levenston herbalists worked in various parts of Glasgow during the 1860s with businesses in London Street, in Park Place in the West End and Nicolson Street in the Gorbals. The London Street premises were actually the site of Samuel Levenston's surgery and it was there that Henry Levenston operated his medical herbalist business for a short time. However, Samuel's use of the premises may actually have finished before Henry began business there. Medical botanists like the Levenstons usually derived most of their income from the poorer classes but qualified practitioners often competed for the same business from the middle classes who wished to keep medical fees to a minimum. (11) They were often ready to try cheaper, and possibly more 'promising' alternatives, which if ineffective were at least likely to be harmless.

In fact the obtaining of a medical degree by Samuel may well have split the family enhancing the natural competition between city doctor and medical botanists. While gaining a medical degree undoubtedly conferred additional merit on the holder some ambitious doctors combined professional reputation-making with the promotion of specific remedies, falling back on that traditional source of income for general practitioners, the drug trade. (12) The medical profession carried on a fierce campaign during the nineteenth century against fringe practice and although they were able to push unorthodox practitioners towards the periphery of medical practice, they were unable to wipe them out. (13) There is no evidence of great prosperity in the Levenston family in Glasgow. Both qualified and unqualified practitioners had to struggle for their livelihoods. (14) Salaries of city general practitioners were only about £150 to £200 annually at the time while that of a parochial medical officer was a meager £15. (15)

In 1864 Samuel Levenston moved his surgery first to West Howard

Street, while living in Hope Street in the city centre, later also

practising there. His name disappears from the Medical Directory in

1881 when he was 60 years old although his surgery address was listed

in the Postal Directory until 1906 when he would have been 85 years

old. Latterly, he lived in the fashionable West End with addresses in

Elmbank Crescent and Lilybank Gardens.

Solomon

Alexander Levenston's (1858-1897) Medical Notebook

The Levenston connection with medical herbalism in Scotland lasted for several decades more. Joseph's son, also named Solomon Alexander Levenston (1858-1897), born in Aberdeen, practised till his death as a medical herbalist in Greenock and other places around Scotland. (16) Joseph had been in correspondence with his brother Solomon in Dublin about sending his son there to act as a medical assistant to his uncle. (17) It is likely that with the young Solomon's botanical practices causing embarrassment to his uncles in Glasgow a move to Dublin would have been widely welcomed. However, the scheme to get young Solomon out of Scotland failed. His father Joseph suggested that it was silly for his son Solomon to leave a "good thing" in Scotland for an uncertainty in Ireland but perhaps brother Solomon would like to have Joseph come over instead to assist him in Dublin!

Of all the family only Michael Jacob and Samuel Levenston were members of the Glasgow Hebrew Congregation which had been founded in 1823, the year of Samuel's birth, when there were probably less than 30 Jews in Glasgow. (18) In addition Samuel was the first secretary of the Masonic Lodge Montefiore when it was founded in 1888 and he had a reputation for his ability to solve communal problems. Samuel Levenston was the first Jewish doctor in Scotland to spend his entire medical career in the city and during his long life, which ended in 1913, both the city and its Jewish community underwent a remarkable growth. (19) Glasgow, with over a million citizens, became the second largest city of the British Empire, while Glasgow Jewry expanded from less than 200 souls when the Levenstons arrived in the 1850s to become the third largest provincial Jewish community in Britain with about 12,000 members.

There was also a strong musical talent in the Levenston family. (20) Solomon' s eldest son Philip Michael became Professor of Music at the Royal Irish Academy of Music in Dublin and two other members of the family in Dublin, Samuel and Joseph, ran a dance academy there, as mentioned by James Joyce in Ulysses. One of the brothers of Solomon and Samuel was a violin teacher in Glasgow while another Henry Levenston worked in Glasgow from 1906 to 1914 as a music teacher and a violinist at the Theatre Royal.

| Items from the Pharmacopeia of Solomon Levenston | |

|---|---|

| (I) for nervous debility | . |

| tinct. ferri. perchlor. | 2 drams |

| glycerine | I ounce |

| inf. quassia | 6 ounces |

| dose: a tablespoon 3 times daily | . |

| . | . |

| (II) "women's friend" | . |

| powdered Bistort Root | 1 ounce |

| powdered cinnamon | 1/2 ounce |

| powdered tormentil | 1 ounce |

| powdered white pond lily | 1/2 ounce |

| powdered Balmory | 1/2 ounce |

| powdered Capsicum | 1/2 drachm |

| dose: a teaspoonful in a teacupful sweetened hot water | . |

| indications: uterine haemorrhages and discharges | . |

| . | . |

| (III) blood mixture for syphilis | . |

| iodide of potass. | 2 drams |

| extract of sarsaparilla | 1 ounce |

| aqua | 7 ounces |

| dose: a tablespoon three times a day | . |

| . | . |

| (IV) infantile anodyne (Price, Walton and Co. Recipe) | . |

| syrup poppies | 1 ounce |

| water of aniseed | 3 ounces |

| brandy | 1/2 ounce |

| dose: a teaspoonful when required for children for teething or for bellyache | . |

| . | . |

| (V) tincture of arnica | . |

| flower of the arnica plant | 2 ounces |

| proof spirits of wine | 1 pint |

| macerate, express and filter; put a tablespoon of the tincture in a half pint of water, soak a linen and apply to the point affected, apply externally for bruises and sprains (it must not be administered internally except by an experienced practitioner). | . |

Levenstons Migrate to the Internet

The Levenston and Stibbe Families (5000 names)

Mike's Martial Arts - 8th Degree Black Belt - San Sho Do

Michael Levenston, Theatre Manager, 1855-1904

Gerald Levenston, born 1914, Toronto, Canada

updated September 16, 2013

cityfarmer@gmail.com